“For precious friends” | BookGo Issue 11 👫

The art of gifting old poems for newborns | Celebrating all things Shakespearean for the Bard’s birthday | New poems from BookGo authors | And what’s up with the doctors in Shakespeare’s plays!?

Happy Friday all! This is our final instalment celebrating all things poetic in honor of National Poetry Month. Here’s what’s in store!

Table of Contents

Poem of the Week: “When to the Sessions of Sweet Silent Thought” by William Shakespeare

New Poetry: “Sea-Things” and “The Starlings” by Callum Tichenor

Feature: “The Agony of Genius: Wasting Time?” by Michael McKinley

New Poetry: “Learning to Live without You” by Michael Sofranko

Feature: “Throw Physic to the Dogs: Did the Bard have a Problem with Doctors?” by Tomas Elliott

Poem of the Week 🖋️

Well, with this week marking the end of National Poetry Month and the celebration of the anniversary of William Shakespeare’s birth on 23 April 1564 and – remarkably – his death on the same day, 52 years later, on 23 April 1616, it’s fitting that there’s a rather Shakespearean theme running throughout our newsletter this week.

To kick off, we thought we would bring you one of our favorite poems from Shakespeare’s cycle of sonnets, Sonnet 30: “When to the Sessions of Sweet Silent Thought,” in which the speaker reflects elegiacally on the passage of time, but finds comfort in the final couplet, in remembering a “dear friend.”

Sonnet 30: “When to the Sessions of Sweet Silent Thought”

By William Shakespeare

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought I summon up remembrance of things past, I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought, And with old woes new wail my dear time's waste: Then can I drown an eye, unus'd to flow, For precious friends hid in death's dateless night, And weep afresh love's long since cancell'd woe, And moan th' expense of many a vanish'd sight; Then can I grieve at grievances foregone, And heavily from woe to woe tell o'er The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan, Which I new pay as if not paid before. But if the while I think on thee, dear friend, All losses are restor'd, and sorrows end.

Bonus: Hear this poem read by Kenneth Branagh on When Love Speaks: The Sonnets (2002)

The sorrows really pile up in that poem, aided by the relentless alliteration (“sweet silent,” “death’s dateless,” “fore-bemoaned moan”), which gives a sense of the ever-increasing weight produced by memory, as we “grieve at grievances foregone.”

This, however, only adds to the poignancy to the final couplet, in which the speaker shakes off some of those grievances not by remembering those things missing from their own life (“the lack of many a thing I sought”) but by reflecting on someone they care about: a “dear friend.”

While it might be too much to imagine that thinking about others could restore “all losses” and put an end to all sorrows, as the final couplet suggests, there is some comfort in the idea that in remembering a dear friend we find some sweetness in our solitude.

Friendship (as much as Shakespeare) is a theme of much of the rest of our feature articles, poems, and writing this week. We’ve got poems and essays from old BookGo friends, and even advice about gifts for any little new friends in your life.

We’re also keen to make new friends ourselves, so if you know of any fellow readers or writers, do introduce us! But this one goes out to you and yours — a newsletter “for precious friends.”

Old Poems for Newbies

By Nancy Merritt Bell

A baby is born, and it is time to pile on the gifts. Here comes the regular onslaught of cute clothes and squeaky toys, maybe even a fancy new Coach Baby Bag or light-weight stroller. But I give books.

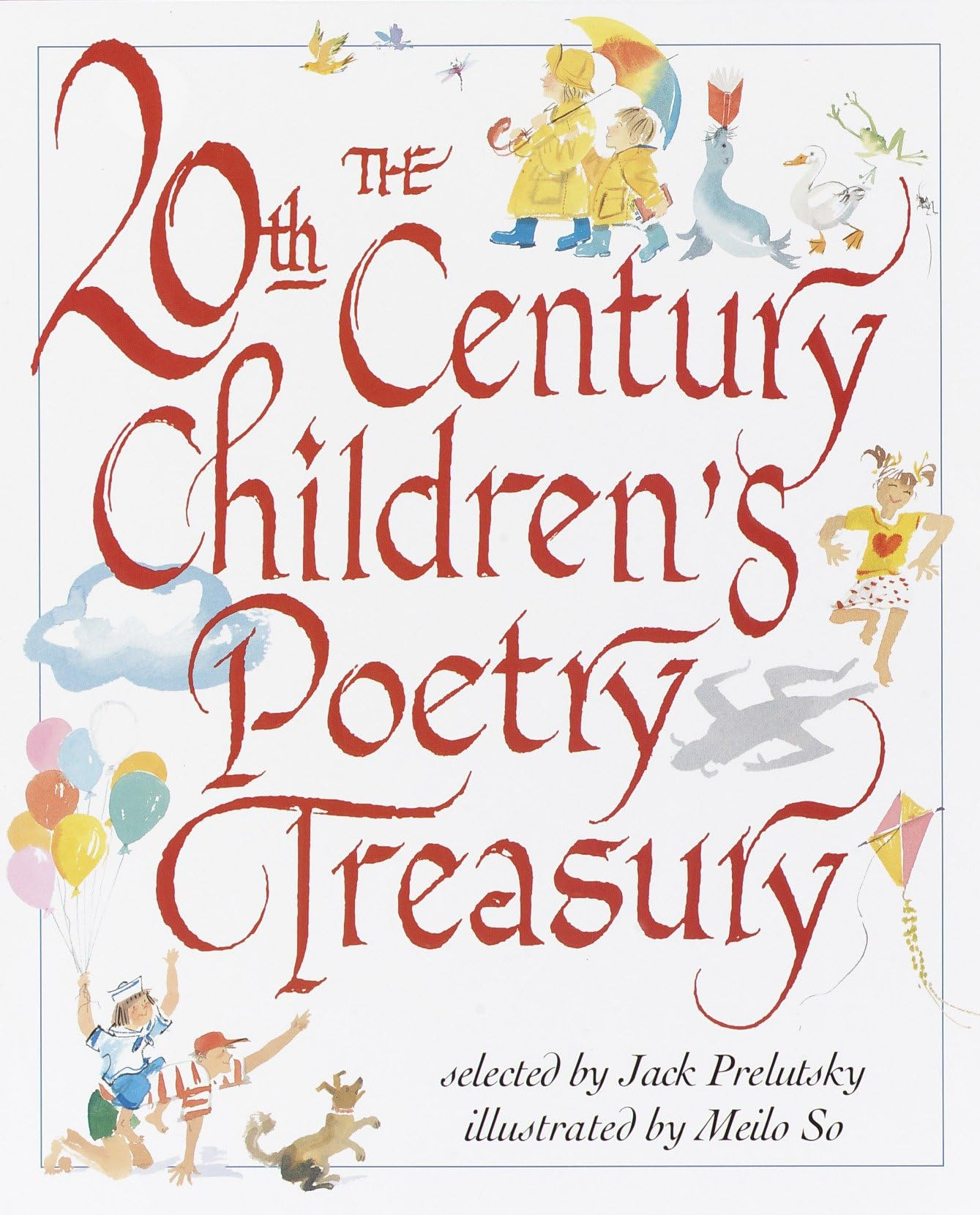

You can never be too young for poetry, even classics like those by A.A. Milne or Dr. Seuss. My favorite is The 20th-Century Children's Poetry Treasury. It is my go-to newbie gift and a virtual starter kit in Kid Lit, published by Knopf Books for Young Readers in 1999. For about twenty bucks you get about 100 poems – a poetic bargain!

But unlike the usual baby gifts of fluffy bunnies and velvety blankets, poetry is not an obvious present. There will not be competition; you will not hear, “Oh, you know, baby Chester is a bit done on poetry: he just got The Iliad, translated by Emily Wilson!” The recent translation is fabulous, and though I’d love to hear this lament, it isn’t coming too soon.

Even so, I must warn you, this poetry book might not always be a welcomed gift. Having recently bestowed this gorgeous tome on a set of new parents, they replied, “Thanks, and we will read it to our baby girl when she understands”. OK, so the guidelines suggest the book is for readers ages 3 to 11. Why wait even three years? As soon as we’re born, we are cooing about language and crying out to be understood.

Not only is any new baby arriving with some language skills, mostly of the wailing kind, but in months, even weeks, she will reply to familiar voices and even familiar words. She will beam when her mama says “Hello,” and when she is struggling – or ‘fussing’ as people like to say – and dad asks her soothingly, “What’s the problem here?” and the babe is soon at ease. She is hearing and responding. At six months to a year, she will even be building up her language skills and can recognize dozens of different words and speakers.

Yes, reading is different, using several different complex processes that require visual acuity as we see letters, then put them together as words, and this also employs memory and retention – let alone the strength and dexterity to handle a three-pound book. But being spoken to, and hearing a series of sounds repeated, and learning how words create meaning can develop daily, and while being read to. Poems engage a wider range of words and sounds.

This poetry treasury, though not too new, is still packed with hilarious poems that are meant to be read out loud as they carry clicks, buzzes, pops and bangs, offering the simple joy of language and sound. Read out loud Donna Lugg Pape’s “The Click Clacker Machine” about a very noisy machine, and add your own clicks and clacks, and tickles, too, and you’ll get some baby smiles. Or more soothing is Charlotte Zolotow’s “Autumn” which is full of lovely long vowels for a musical read.

Help the poems come alive and give them an emotional component—and a positive connection to books--by rocking your baby in time to the poem’s rhythm. Hold your baby close and let her touch your mouth to explore its moving shapes as you make those silly clicks and clacks. Another delightful poem for the very new and the parent too is A.A. Milne’s “The More it Snows” where the fun is built in as you get to repeat the goofy words “tiddely-pom, tiddely-pom.”

It is also a great book to grow on. When your tot is one or two and alert to different sounds, you’ll enjoy the play of language in “Sick” by Marci Ridlon—written with the stuffy nose in mind. Or even at bathtime with bubbles in the tub, play with bubbles when you read the poem “Bubbles” by Deborah Chandra.

When your tot has a fuller language command there are loads of poems here which are laugh-out-loud funny for the small set and us big ones, too, like “Be Glad Your Nose is on Your Face” by poet Jack Prelutsky, who is also the book’s editor. This silly poem imagines the nose in odd and unseemly placements, under your smelly armpit, or in your ear and sneezing your brain away. There are also thought poems about tougher moments, about Mondays and bad moods, and ones full of valuable life skills about anger and the loneliness that can come with it in “Mad Song” by Myra Cohn Livingston.

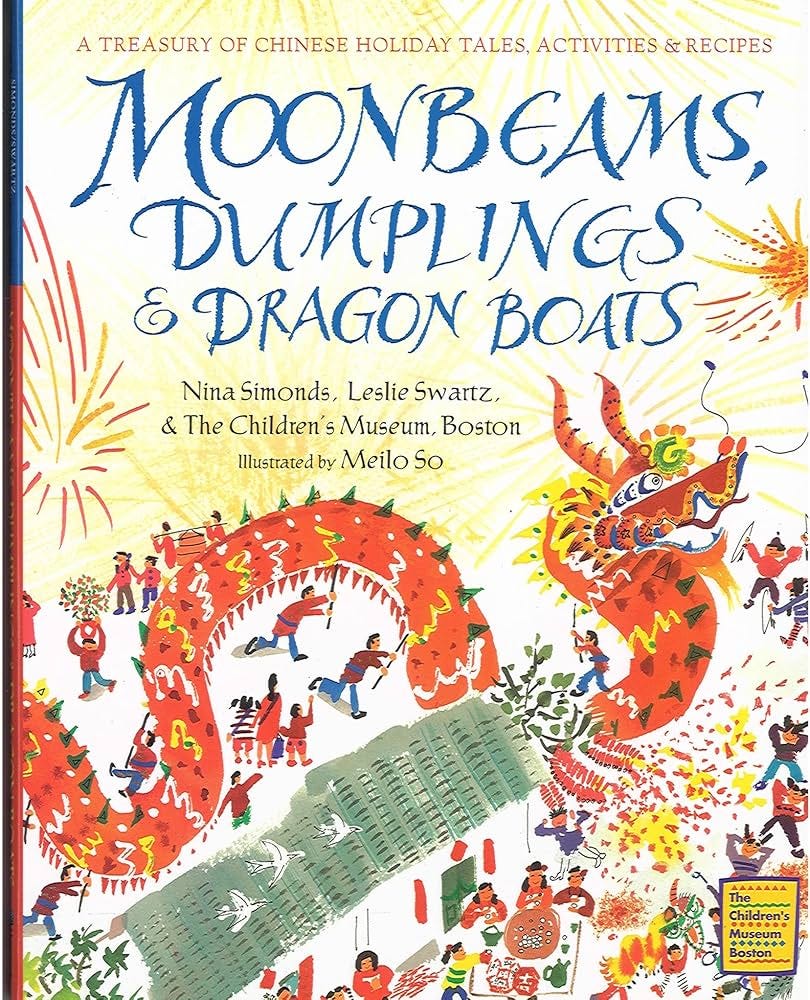

All of the 87 pages of poems, plus the introduction--and even the index pages-- come with the bouncy watercolor images by Meilo So. This amazing illustrator has a great range of talent, adding pictures to award-winning books such as A Treasury of Chinese Holiday Tales, and The White Swan Express: A Story about Adoption. So’s watercolors cover a range of events and feelings in this book to help your tot imagine where your nose is in “Be Glad Your Nose is on Your Face” by poet Jack Prelutsky, and see the snow pile high in “The More it Snows” by A.A. Milne.

The poetry book is also a safe bet as a baby gift. That fuzzy bunny tail could come off that stuffy and become a choking hazard. It will age better, too. In weeks the gift of the cute pink cap will be ratty and ripped. And in years to come, that cap will be outgrown entirely, if it survives, but the poetry treasury will be remembered. In fact, many of my Book Babies who were given the poetry treasury as a newbie are now in their teen years and still often cuddle up with a book of poetry as they did when they were tots – yes, they read poems instead of texting friends, or playing The Sims 4.

These days, I get to read my daughter’s university papers on W.B. Yeats, and I’m left in awe at how she relates the poet’s glorious talent to politics and to the human needs for myth, making me want to read Yeats’s poems again. I’m thrilled she’ll be studying Shakespeare next year—I can hardly wait for those papers. Even now, she always remembers her first book of poetry, which was a wonderful gift from a dear friend, which got her hooked on poems: The 20th-Century Children's Poetry Treasury.

— Nancy

Two Poems

By Callum Tichenor

“Sea Things”

A sudden shell in sand Arrested my dull pace And I took it in my hand And I felt the empty case And I pocketed it while I watched the dark waves lace Combed over mile to mile Aspiring too far – And I smiled a nervous smile To know what sea-things are.

“The Starlings”

Like oily scales upon a snake The starlings dance the past few days At evening; arabesque-exhale -– A black and atomed livingness. Against the dead grey clouds they press, On angels’ wings they streamly sail. In beauty they converge and craze, In beauty they spread out and break.

Bonus: Starling Super Swarms in Rome

The Agony of Genius – Wasting Time?

By Michael McKinley

“I wasted time and now doth time waste me.” That gem comes from William Shakespeare’s play Richard II, when the king is imprisoned and is reflecting on what he has not done with his life. But which writer has not felt those same words acutely when faced with a deadline, or a blank page?

I want to keep this idea to the writerly caste, though it applies to us all, for in the spirit of my Hibernian ancestors, I am acutely aware of the fact that time runs out on us all.

That said, who knows how much time we have, really? Unless, of course, you are writing to a deadline. And then you have to deliver “on time” or be scolded by an editor, and writers will often discover the same sense of editorial urgency does not apply to being paid for that which they delivered on time. What would Steven Hawking say about that?

Probably not “Time passes, people marry and die, Pinkerton does not return,” which is a paraphrase of Woody Allen’s take on Madame Butterfly, but it does connect to Richard II in the sense of deciding when has the time passed been wasted?

I think the answer is only if you are in a position to do something in the time that has passed and didn’t or couldn’t do it, especially if you yourself were wasted.

However, this then raises the idea of waste. What exactly is wasted time? If you sit on a beach for days and stare at the ocean and daydream, which is good for you, the psychs tell us, and better still, it makes you happy, is that wasted time?

If you planned to retire at age 65 and are now rethinking that maybe age 85 or beyond is more likely, is that time that you had initially carved out for your retirement “wasted” by not being “used” for doing “nothing?”

This idea cuts to the heart of our Puritanical notion of time, which decrees that every second must be accounted for in some worthy labor which, for them, was devoted to the divine, and for us, can be devoted to the benign. Either way, time is regarded as a valuable commodity, and so not using it properly is “wasting” it. But again, what is its proper use?

Our time belongs to each one of us. We do not know how much of it we have, but we can do with it what we want. We can spend ten years writing a brilliant novel that no one will read, let alone publish, and is that wasted time? Or we can spend two weeks writing a trashy novel that everyone reads. Are those readers wasting their time? Did you waste it writing trash?

I don’t know. Only the “owner” of the time knows if there was something of more value to them, or to society, that they could have been doing in that time that they have spent. It’s why Richard II says what he says. He knows that there was something of more value he could have done, and he did not do it.

Of course, since time runs out, we can never really say that time was wasted. It was spent. We made a choice. And having that choice is what makes time valuable.

So, if you have a great idea for a book, then spend time to write it. It will take as long as it takes. It will be of value to you. And your time spent, no matter what, will be yours—until time runs out. And no matter how great your book is, time will run out on it, for one day the sun will burn out so time really will run out for everything under the sun. Happy 461st birthday William Shakespeare, on April 23, by the way. You didn’t waste your time, and yet…

— Michael

🎊 Fame and Glory! 🏆

If you too find yourself trudging through the agony of genius, or if you know of any silent geniuses who deserve to have their life story told, in a book or in a film, or both, please let us know! We'll take it from there and get their name in lights!

Learning to Live without You

By Michael Sofranko

Many of us share the experience of finding a voice message still on our phone after someone beloved has passed. My dear friend, Linda, and I remained in touch for 40 years. We began romantically in San Francisco, but slowly, the romance dwindled, and the friendship deepened. At times we lived thousands of miles away from each other, and what a joy it was, for each of us, to feel so totally unjudged, accepted, and yes, loved, each time we spoke. When it was urgent, we left messages that voiced that need; but usually it was a casual, Hello again, how are you doing? In those cases, we might return the call in a matter of days, but just as likely in a matter of weeks.

I received one of those messages from Linda in late September 2022. By the end of November, a little bothered I had not yet responded, one night I asked my partner if I had ever told her about Linda, who owned a very successful antique business in the middle of Amish country in southeastern Pennsylvania. When she said, Oh, you mean the woman who recently died,” I was shocked. She’d learned of Linda’s passing weeks earlier on Instagram. She assumed I knew.

A chasm, an emptiness, opened inside me, as if my stomach were suddenly missing. This poem is my attempt to reconcile with Linda, to grieve for her, and to recapture when I can, what I can, of her. Her message remains on my phone, a voice full of gaiety and life. I cannot bring myself to delete it, not even after all this time.

“Learning to Live without You”

~ For Linda

I received a message I never returned In time. Then you never returned At all. I cannot erase Your voice. Years ago, when I stood behind you On a cliff as we faced the Pacific The wind howling onshore Blew your words Into my ears. They rang like two shells With the sound of the sea Inside them. It never stopped. When the wind whipped back Your hair I moved closer So that wisps of it Would play against my face. We were dreamers then. Now I have a message I never returned In time. And you, who will never Return at all. No guitar. No songs at dusk. No prayers inside The small, locked box I keep. I am losing you slowly. I am losing you Over & over. Under several layers Of blankets, tonight I listen to the bayou, And the voices on the ravine Full of the wailing lament Of everything living In this false spring. And I still hope to find you Somewhere in the unreadable Murmur of insects Screeching of their needs Through the canopy of trees.

— Michael

Michael Sofranko is an internationally acclaimed writer, editor, poet, and professor. He has received The Antonio Machado Prize and numerous other recognitions. Dedicated to mentoring new, as well as experienced authors, he earned an MFA from the Writers Workshop at University of Iowa and attended the PhD program at the University of Houston. He has led Writing Workshops in the U.S. and Europe, including at Cambridge University.

Throw Physic to the Dogs: Did the Bard have a Problem with Doctors?

Late on in Shakespeare’s Scottish play, as the lust for power of the play’s scheming couple sickens the political health of Scotland and lays waste to Lady Macbeth’s mind, her partner in crime (perhaps displaying the love and care that prompted Harold Bloom to describe the Macbeths as “the happiest couple in Shakespeare), turns desperately to a doctor to cure her:

MACBETH: How does your patient, doctor? DOCTOR: Not so sick, my lord, As she is troubled with thick coming fancies, That keep her from her rest. MACBETH: Cure her of that. Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, Pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, Raze out the written troubles of the brain And with some sweet oblivious antidote Cleanse the stuff'd bosom of that perilous stuff Which weighs upon the heart?

Of course, there’s nothing the doctor can do. He laments:

DOCTOR: Therein the patient Must minister to himself.

At which point Macbeth – not out of character – quickly grows impatient!

MACBETH: Throw physic to the dogs; I'll none of it.

Now perhaps this frustration with a medical professional makes sense in the context of the play, as Macbeth by this point is rapidly spiralling out of control in the play’s final act, desperately seeking solutions to save his crown and his partner in crime. Perhaps we just accept that there is nothing the doctor can do, and we share in Macbeth’s nihilistic frustration, despairing of all hope in the power of what he calls “physic” – the work of the physician.

But when we come to think about it, it is a curious theme throughout Shakespeare’s plays, that members of the medical profession appear rather incompetent! There are eight doctors in total in Shakespeare’s thirty-eight plays. Those in the comedies are (perhaps unsurprisingly) the subjects of ridicule. Doctor Caius in The Merry Wives of Windsor, for example, is referred to as “Castalion-King-Urinal,” satirising the rather pronounced obsession that Elizabethan doctors seem to have had with studying their patients’ urine.

In the tragedies, meanwhile (and again, perhaps unsurprisingly), the doctors are rather incompetent, unable to prevent the impending doom of death that will soon smother all and sundry. In King Lear, Cordelia’s hope that the doctor will “cure this great breach” in her father’s “abused nature” does not, of course, come to fruition. In Romeo and Juliet, the medical profession comes further into disrepute through the figure of the Apothecary. The equivalent of a modern-day pharmacist, this drug pedlar provides Romeo with the poison he uses to commit suicide. While he knows that it’s illegal – not to mention morally questionable – to sell such poison to a teenager (“Such mortal drugs I have, but Mantua’s law / Is death to any he that utters it”), he does so anyway just to make some cash: “My poverty, but not my will, consents.”

All of which leads us to wonder… did Shakespeare have a problem with doctors!? His daughter, Susanna, married a doctor named John Hall in 1607, and Hall had a practice in their hometown of Stratford. What might Shakespeare’s son-in-law have made of the Bard’s representation of the medical profession on stage…?

Of course, we’ll never know! But recalling Shakespeare’s array of medical characters reminds us that medical plots, doctors, drugs, sickness, and races to find a cure have always served as compelling sources of inspiration for poets.

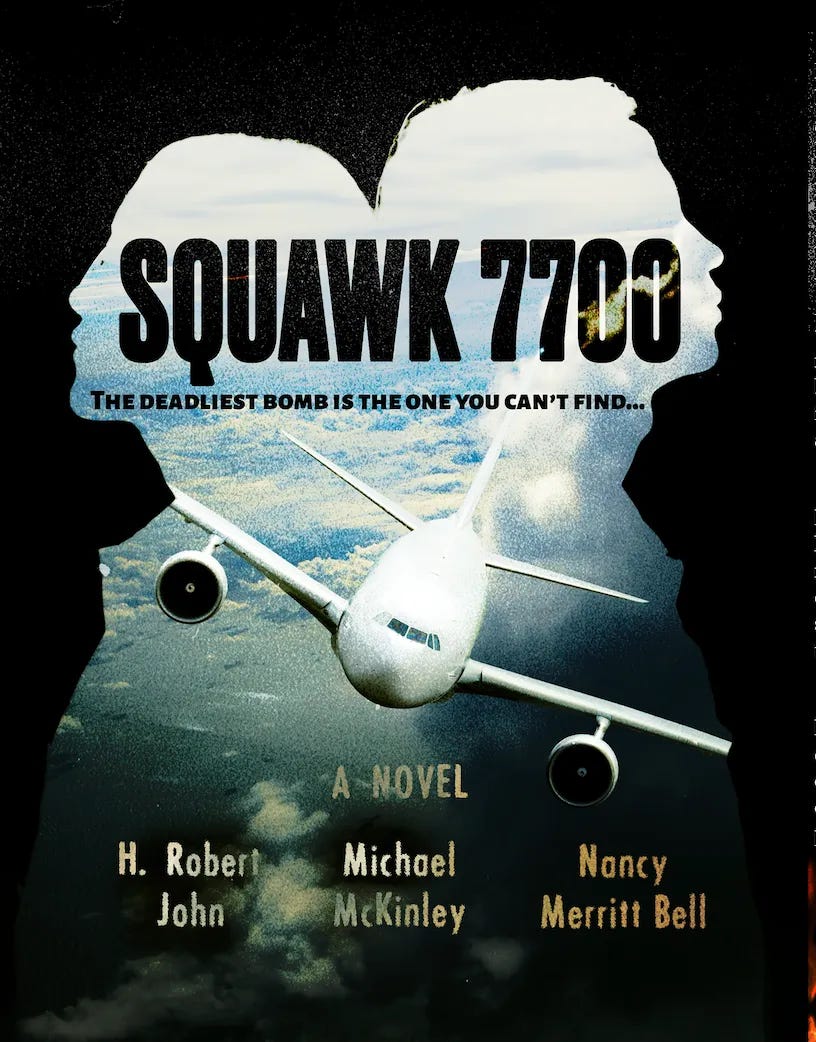

We think the same is true today, and that’s why we’re continuing to celebrate the overlaps between medicine and literature in preparation for the release of Squawk 7700, written in collaboration with neurosurgeon H. Robert John. The first chapter is available to read for free on our website now!

That’s all for this week! We hope you enjoy the final few days of National Poetry Month. We’re just getting started on Substack, so please do give us a hand by liking, sharing, subscribing!

See you next Friday! 💖