“Live alone... and like it...” When you've got books in your life that is! 💁♀️

Happy world poetry day! | Exploring forgotten female authors | "Squawk 7700" in production | What goes around comes around in the world of writing | And more...!

Hello everyone and welcome to another Friday round-up from BookGo. First and foremost, happy world poetry day! We’ve got words from poets past and present for you to ponder today. Plus, if you’re reading this, then it also means you survived the ides of March, so that’s one less thing to worry about this week, I guess! 😮💨

Let’s take a look at what’s in store.

First, Nancy continues our celebrations of women writers with a deep dive into some of the overlooked or forgotten female authors of the twentieth century. Nancy reconstructs the alphabet of female authors all the way from the A of Margaret Atwood to the Z of Zora Neale Hurston! Nancy brings us the words of advice we’re living by this week, from oft-overlooked self-help author Marjorie Hillis, who reminded readers in the early-twentieth-century to learn to “live alone and like it!” We find the only way to do that is with some quality writing to keep you company!

To that end, in our FreeReads section, we’ve got yet another poem to bring you from the BookGo family. YA poet and teacher Sarah Fymme brings us a short and funny reflection on the arrival of spring in the irreverent “Spring Stinks”! 📚

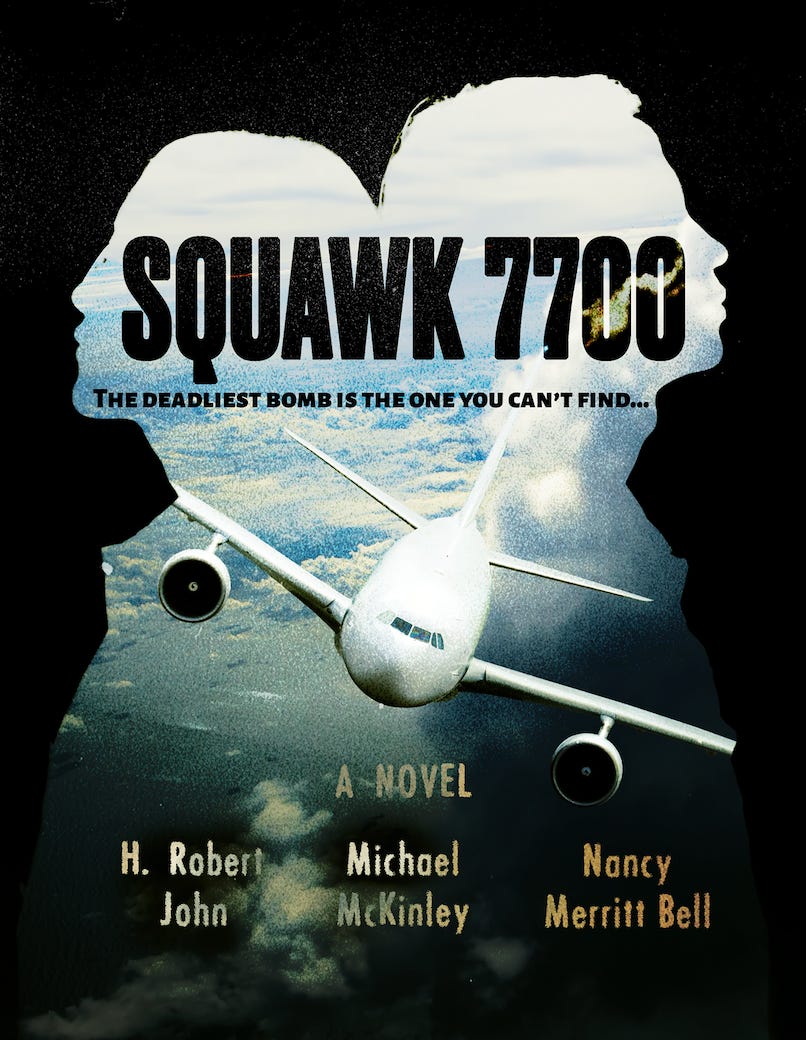

And speaking of poetry, what have the poems of the nineteenth-century romantic poet John Keats and our upcoming thriller novel Squawk 7700 got in common? We’re glad you asked: they were both written by medics, of course! Squawk 7700 was written by Dr. Robert H. John, and to celebrate it officially going into print production (🤩), we’re kicking off a tour through the long history of medical doctors who also wrote literature. Did you know Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a doctor? What about Anton Chekhov? William Carlos Williams? Stay tuned for more insights into marvellous medical writers in the weeks and months to come. 🩺

There are even more insights into the trials and tribulations of authors this week from Michael in the Agony of Genius. Taking inspiration from the tale of what happened when the great American novelist John Steinbeck had half his manuscript for Of Mice and Men eaten by his dog (turns out sometimes the “dog-ate-my-homework” excuse really is true!), Michael reminds us that everything we write will eventually come back round to us again – just hope it doesn’t look like too much of a dog’s breakfast when it does. 🐶

Then, to ease some of the pains of that writing life, Tom’s got his regular suggestions of what to watch, read, and sip this week as spring peaks it’s head out from behind the clouds. ☀️

As always, we hope you’ll find something for everyone in our newsletters, but we’re always looking to connect with new people and hear from more voices. So, if you like what we’re doing, please share with your friends and family, and if you’ve got something to write or share about books, publishing, or anything at all, please get in touch! We’d love to feature you or your work in a future newsletter!

For now though, let’s get BookGoing! 🌻

Gone Girl… And Welcome Back!

Women Writers of the Last Century Lost and Found

By Nancy Merritt Bell

In high school, I studied all the “important women writers” – A to B – so the joke went. The short list at the time included not Jane Austen but Margaret Atwood and Charlotte Brontë. Atwood’s work was a grudging nationalistic addition because I was slogging through a Canadian high school.

Today the alphabet of female writers is wonderfully packed. Tomorrow the list will be full to overflowing: lost writers or little-known-or even the not-yet-famous-enough writers-are being found and put front and center on bookshelves and reading lists. One of the finders is my own sister, a PhD candidate in Art in Culture at Western U, who told me, “You simply have to read Clarice Lispector!” Of course, I told her, “I am simply too busy.”

Thank the spirit of Sappho I was not utterly cross-eyed, stumble-down busy, so I picked up Near to the Wild Heart, the first novel by Lispector, a Polish-born Brazilian writer (1920-1977), and I could not put it down. In fact, I had to lie down as I read, left prone by the gorgeous, very internal prose which was also a very hot read. Next on my recovery list is Lispector’s great mystic novel The Passion According to G.H., followed by the novel many consider to be her masterpiece, Água Viva.

Often the saviors of our authors aren’t sisters but authors themselves. The witty and wise American writer, critic and historian, Joanna Scutts (now living the Great American ex-pat life in Paris) happily fell down the rabbit hole on the hunt for Marjorie Hillis (1887-1971), an honest, hilarious and almost forgotten 1930s self-help writer. After Scutts’s father died suddenly and she found herself looking at turning thirty very much alone, she also found Hillis’s 1936 bestseller, Live Alone and Like It. In it, Hillis takes on the great Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, but instead of the “truth universally acknowledged” as it was for Elizabeth Bennet, Hillis’s heroine is from the non-marrying generation. She writes: “the chances are that at some time in your life, possibly only now and then between husbands, you will find yourself settling down to a solitary existence.” Learn to love your life alone, Hillis insists. The rest of the book is a comic look at taking charge of your own pleasure – from physical to fashion to financial. Written almost a century ago, Hillis’s work adds a much needed voice to the rather empty choir of female voices of the first part of the 20th century, telling us how we even got to this century.

The chances are that at some time in your life, possibly only now and then between husbands, you will find yourself settling down to a solitary existence.

~ Marjorie Hillis, Live Alone and Like It (1936)

It was the author Alice Walker who resurrected the work of Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960). The Howard University-educated Hurston, who went on to study and research at Barnard College and Columbia University, was a quadruple threat, being an author who was also an anthropologist, folklorist, and documentary filmmaker. She wrote four novels in her life, all set in the 20th-century American South and intensely focused on racial conflict. The best known of her novels is Their Eyes Were Watching God, published in 1937, was almost buried under a barrage of criticism for its unsympathetic-AKA a painfully honest-portrayal of both Black and white characters. But the book, thanks to the support of Walker and other authors, has a central place now in the literature of the Harlem Renaissance, and has even been enshrined on the must-read list in high schools. (If you want to dip into Hurston’s work, she has over 50 short stories, each one aching with insights into the racism of the Southern US).

New York Times critic and Muck Rack regular, Parul Sehgal has pronounced this moment to be a bona fide movement: women writers are championing the lost and neglected women’s voices of the pre-Didion-Plath-Sontag early 20th Century. Adding muscle and money and plain old “official-dom” to their efforts are trailblazing publishers like the Feminist Press and UK’s Virago Press. They all share a mission to add to the chorus of authors and turn up the volume on those who speak on contemporary feminism, while also enriching the literary canon from Atwood to Zora, and beyond.

Why don’t we as we celebrate Women’s History Month and reclaim our writers of the past just skip old Geoffrey Chaucer and go for Julian of Norwich or Margery Kempe, and let’s forget Homer and go for Sappho. Ladies, get out your literary shovels. We have a millennium or two to dig into!

— Nancy

🆓📚🎉 BookGo FreeReads 🆓📚🎉

In BookGo FreeReads, we feature excerpts and full works from BookGo’s wider network of family and friends.

SPRING STINKS!

By Sarah Fymme

My winter frozen nose still knows Through sniffly snorts and wheezy blows The earth will stink in Spring melt snows! With ice gray crusts and rainy spit, With murky wet in wooly mitt, And chocolate yuck in puddle mud, And sticky ick on street curb crud. What December dog done in fresh snowbank Now April’s here reeks twice as rank, As ancient toilet topped with death, This Spring-new world wakes morning breath! The rising stinks of yuck and poo, Are the first and worst smells of the New.

Sarah Fymme is a New York City-based teacher, writer and YA poet: Sara is deaf and a member of the Deaf Poet’s Society. Her work has been published in Private Press.

The Doctors are in… Or, what the poems of John Keats and Squawk 7700 have in common

— By Tom Elliott

BookGo and YourBook are very excited to announce that Squawk 7700 is officially in production! This medical thriller was written by Michael McKinley, Nancy Merrit Bell and H. Robert John — John’s many years of experience as a neurosurgeon provide the driving force of its fast-paced plot. To celebrate the release of Squawk 7700, we’re kicking off a series of explorations of other doctors-come-authors, and for world poetry day, where better to start than with the romantic poet prodigy John Keats. 🩺

Many people think of John Keats (1795–1821), the pale-faced English poet of the late romantic period, as one of the consummate poets of the imagination, frequently drifting off in his works into the dreamy realms of nature and the imagination. Take these lines from his 1819 “Ode on Indolence,” for example:

From “Ode on Indolence” by John Keats (1819)

The blissful cloud of summer-indolence Benumb’d my eyes; my pulse grew less and less; Pain had no sting, and pleasure’s wreath no flower: O, why did ye not melt, and leave my sense Unhaunted quite of all but—nothingness?

Ahh. Can’t one just picture oneself reclining in the sun-soaked meadows of the English countryside with nothing else to do but pen a few lines of poetry? I love the stasis, the idea of a world where “pain [has] no sting,” and we can leave all our cares and “sense” behind. In perfect indolence, we find ourselves, as Keats quite beautifully puts it: “unhaunted.”

Everything here seems to be about leaving the world behind, escaping into the imagination. And elsewhere we find similar themes. Keats suggests much the same in his description of being carried away into other worlds through the adventure of reading. See, for example, his quite wonderful sonnet, which he wrote age 21(!), about reading a translation of Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad by the seventeenth-century poet George Chapman:

“On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” by John Keats (1816)

Much have I travell’d in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

That deep-brow’d Homer ruled as his demesne;

Yet did I never breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star’d at the Pacific—and all his men

Look’d at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien. Again here, we get carried off into other worlds as the speaker of the poem goes travelling in “the realms of gold.” We’re getting the picture, then, of Keats as someone who doesn’t have much of an eye on his present surroundings; he’s a “watcher of the skies,” wandering, like one of his spiritual forebears once did, “lonely as a cloud.”

We might wonder whether this ever proved a problem for Keats in the day job he had when he was writing “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” – Keats at this time was a surgeon’s pupil and dresser at Guy’s Hospital in London! Dressers were an integral part of hospital operations, and Keats would have been responsible for assisting with surgeries and caring for pre- and post-op patients. How happy would his medical professors have been if he spent his time watching the skies when his patient was about to go under the knife?

However, while a lot of Keats’ poetry does describe a mystical world of the imagination, free from the pressures of everyday reality (and certainly the pressures of medical school!), elsewhere we find instances of Keats’ medical training and knowledge infiltrating his writing. Does not his careful description of the power of hemlock in “Ode to a Nightingale,” for example, suggest a physician’s (as much as a romantic poet’s) view of the processes of anaesthesia:

From “Ode to a Nightingale” by John Keats (1819)

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunkAs well as the kind of opium-infused trips of which the English romantic poets were so fond (see Thomas de Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium Eater for the best example) Keats’ description here also surely reminds us of the many patients that he would have seen “etherized upon a table” (as the later poet T. S. Eliot, also a working professional, put it). It does not seem like too much of a leap to think that Keats’ many hours spent tending to patients at Guy’s Hospital and his extensive familiarity with the power of drugs and medicine are behind this description of a soporific journey into Lethe.

In fact, according to Hrileena Goth, editor and publisher of John Keats’ Medical Notebooks (2020), everywhere in Keats’ writing we see evidence of the language of medicine, with lectures he attended on the latest developments in neurobiology and the nervous system, for example, reappearing in his description of “the wreath’d trellis of the working brain” in the “Ode to Psyche,” or the descriptions of a “palsied chill… ascending quick to put cold grasp / Upon those streams that pulse beside the throat” recalling patient convulsions in The Fall of Hyperion. The language and knowledge of medicine, in other words, was central to Keats’ ability to craft a compelling visual image and render it in poetic terms.

And this is true of medical writers today! Some of the most gripping and convincing writing, whether in poetry and prose, uses the specialist language and knowledge of different careers and professions to bring a story to life. Squawk 7700, debuting soon with BookGo and YourBook, features Sarah Hart, a third-year medical student following the same career as her father. It’s Sarah’s medical training that allows her to solve an urgent mystery: how could a passenger pass exhaustive screening protocols and still do catastrophic harm to an aircraft in flight? Turns out the answer was already there in her anatomy classes, just as it was for Keats and his poetry.

At BookGo, we see stories everywhere, in hospitals, businesses, courtrooms, and more – that’s why we work with writers from all different professions and parts of the world. If you’ve got an idea for a story based on your own knowledge and experience, let us know – We’d love to help you tell it!

— Tom

The Agony of Genius: From John Steinbeck to Aesop’s Fables and back!

By Michael McKinley

In May 1936, the American literary titan John Steinbeck wrote a startling note to his editor, Elizabeth Otis.

Minor tragedy stalked. My setter pup, left alone one night, made confetti of about half of my manuscript book. Two months’ work to do over again. It set me back. There was no other draft. I was pretty mad, but the poor little fellow may have been acting critically. I didn’t want to ruin a good dog for a manuscript I’m not sure is good at all. He only got an ordinary spanking … I’m not sure Toby didn’t know what he was doing when he ate the first draft. I have promoted Toby-dog to be a lieutenant-colonel in charge of literature.

The book that Steinbeck’s Irish setter dog Toby ate was Of Mice and Men, Steinbeck’s novella about racism, prejudice against the mentally fragile, and personal freedom. The novella went on to be a great success and was made into a film no less than three times.

This story, while true, summons up another thought, one about other literary gems, in need of a dog like Toby not so much to eat them, but to fetch them back to their original purveyor. In other words, there was no Lieutenant Colonel Toby around to digest the truth of the origin story.

Consider this one: “God helps those who help themselves.”

Everyone knows that this staple idea of the Christian world (and maybe beyond it) comes from the Bible.

Then you need to start asking: is it from the Hebrew Bible, aka the Old Testament? Or is it from the New Testament, which chronicles the life and teaching of Jesus, and the work of his apostles, and St. Paul, after Jesus was gone?

A little thought will make you conclude that the essence of Christianity is helping those who cannot help themselves. So, not the New Testament. The Old Testament goes there, too, with the Book of Isaiah, 25:4 telling us that God has been “… a stronghold to the poor, a stronghold to the needy in his distress, a shelter from the storm and a shade from the heat; for the breath of the ruthless is like a storm against a wall…”

Toby! Fetch!

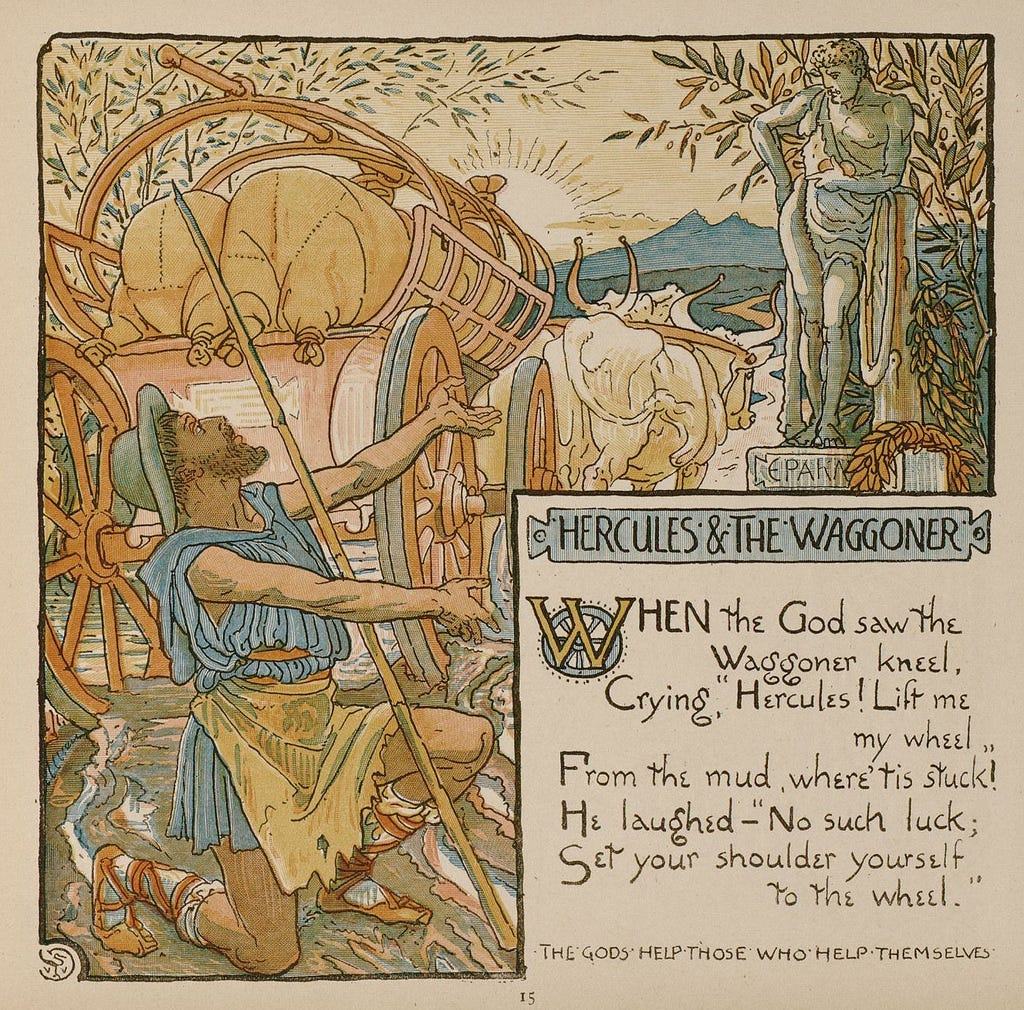

This core idea about divine assistance to “we who do” comes not from the Bible at all. It is usually attributed to Ben Franklin’s “Poor Richard’s Almanac” (1757) but thank you Toby, it comes from Aesop, the 7th century BCE Greek writer. Indeed, it comes from the moral of “Hercules and the Waggoner,” one of Aesop’s Fables.

A Waggoner was once driving a heavy load along a very muddy way. At last he came to a part of the road where the wheels sank half-way into the mire, and the more the horses pulled, the deeper sank the wheels. So the Waggoner threw down his whip, and knelt down and prayed to Hercules the Strong.

"O Hercules, help me in this my hour of distress," quoth he.

But Hercules appeared to him, and said:

"Tut, man, don't sprawl there. Get up and put your shoulder to the wheel."

So, Hercules, the god, would help the Waggoner only if he put his shoulder into it.

However, the fact that this expression has been digested as a core idea of Christianity makes the fact that it came from a pagan society which worshipped many gods for very particular reasons seem as if some Greek version of Toby had eaten Aesop’s fable and then time-traveled to spew it up at the feet of Ben Franklin, whose use of it became corrupted as a Christian ideal.

All of which is to say that everything we write will one day vanish, when the sun burns out, when a dog eats our manuscript, when all the Wi-Fi (and cloud uploads) crash due to whatever technical or human fault, or when it gets misattributed to some other writer, and we are erased from the picture. Knowing this should not agonize the writer but should add a sense of adventure to the whole process, as well as one of humor. Put it all down on paper (or in the ether) and what happens to what you wrote is ultimately beyond your control. That fact alone should free us up to write whatever moves us, because, like Aesop, it could one day become fabulous.

— Michael

Watch One 📺, Read One 📖, Sip One 🍺

By Tomas Elliott

Another week, another round up of something to watch, something to read, and something to savor them with over the course of the weekend.

📺 One to watch: Adolescence, directed by Philip Barantini (2025)

How could it be anything else than the TV show that’s got everyone talking and has taken Netflix’s number one spot in the UK and the US this week? In the US, Margaret Lyons in The New York Times called the third episode of this four-episode mini-series “one of the more fascinating hours of TV I’ve seen in a long time.” Meanwhile, in the UK, Michael Hogan of The Guardian called it “powerful TV that could save lives.” The series explores the gut-wrenching horror stories that seem all too prevalent in our news cycles these days, detailing the violent crimes of adolescents. In this case, the adolescent in question is Jamie (Owen Cooper), who is arrested on suspicion of murdering a female classmate.

The narrative premise is highly compelling and feels particularly urgent right now, given increasing worries over the effects of influencers like Andrew Tate on the increase of violent crimes. It was developed by one of a slew of great actors from what is surely another golden era in British television, Stephen Graham (who also stars as Jamie’s father, Eddie), in collaboration with the playwright Jack Thorne, responsible for other high-profile collaborations and adaptations (including the stage version of Harry Potter and The Cursed Child with J. K. Rowling and the TV series of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials novels).

What really makes this TV show tick, though, and will get your heart racing for four straight hours of watching (because, let’s face it, you’re not not going to binge it) is the form it takes, with each episode being shot in a single take! The show brings back together the production team for Stephen Graham’s masterful 2019 film Boiling Point, which was similarly shot in a single take and remains one of the best pieces of cinema I’ve seen in recent years. Like Boiling Point, Adolescence is directed by Philip Barantini with Matthew Lewis as the cinematographer, and I think their achievement is even more spectacular this time around.

So if you haven’t yet seen it, check it out for the content but stay for the form. And if you missed out on Boiling Point then now’s as good a time as any to go back to that as well. In fact, maybe I’ll do that now…

Adolescence is streaming on Netflix, and you can check out the trailer here:

📖 One to read: The Years, written by Annie Ernaux (2008), translated by Alison L. Strayer (2018)

Alongside the hard-hitting, all-in-the-present, here-and-now narrative of Adolescence, I’ve been engrossed in a work that runs at quite a different pace this week: The Years (Les Années) by the winner of the 2022 Nobel Prize for literature Annie Ernaux, which was translated into English by Alison L. Strayer in 2018. Covering a period from 1941 to 2006, the memoir is a fascinating weaving together of the private memories of its narrator with the public history that defined the second half of the twentieth century. I hope it doesn’t sound too strange to say (I mean it as a compliment) that it felt like reading a mash-up of Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start the Fire” and Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Ernaux has a brilliant ability to evoke the essence of times past that so many of us remember (or imagine we remember), all while filtering it through the undeniably unique experiences of a single woman’s life.

🍺 One to sip: Delirium Tremens, Blond Beer, Ghent, Belgium

My tipple of choice this week is one close to my heart (and my person) since I’m visiting Belgium and amusing myself mainly by sampling from the almost unmatched range of beers that the country has to offer.

Beer has been brewed in Belgium since at least the Roman period, with archaeologists having unearthed evidence of a brewery dating from the 3rd or 4th century C.E. Things really got going in the medieval period, though, particularly in the monasteries run by Trappist monks, which is nowadays what accounts for much of the country’s justly deserved fame as a beer-drinker’s paradise. It wasn’t actually until the late-nineteenth century that Trappist beer-making moved outside the monastery and came to be a hit with the general public, when the monks of Chimay produced a brown beer for commercial consumption, but since then Belgian beer has gone on to dominate worldwide sales and be cherished throughout Europe and beyond.

My recommendation, which you’ll sometimes see in specialist beer stores throughout the US and England, is Delirium Tremens. Somewhat unfortunately named for the shakes experienced by alcoholics, the beer itself is quite remarkable: not overpowering and subtly malty, its smooth and worryingly drinkable for a beer that’s 8.5% strength!

Serve it in the Ghent-based brewery’s iconic elephant-bedecked, trunk-shaped glass, and savor what more than a thousand years of brewing practice can achieve!

That’s all for now! We love to hear from our readers, so let us know your stories and responses in the comments below, and please give us a hand by liking, sharing, and –if you haven’t already – subscribing to BookGo.

See you next Friday! 💖